Sadly, historically, women have been overlooked and sometimes intentionally dismissed and ignored, especially working-class women. In the field of genealogy, I suppose there is less of a chance of this discrimination, at least to an extent, as there is always a desire to trace back as much as physically possible, but when maiden names are unable to be found, and women are simply recorded as ‘Mrs. John Smith’, it can become near impossible to trace their stories. So they become ignored or misrepresented, and I find this to be such a shame.

With this point in mind, it would be easy to dismiss Bridget Cook, my Great Great Great Grandmother, as being John’s wife, George’s daughter, or Charles’ widow. However, this overlooks her story that, despite being lost to time temporarily due to some of the reasons mentioned above, truly exemplifies a woman driven by determination, grit and a quest for survival in a cruel and uncaring world.

Bridget was likely born in 1849, most likely in Monkwearmouth, Sunderland. She was the daughter of George Cook and his wife Judith McMahon, both Irish immigrants who originated from County Louth. They married almost certainly in the 1840s, before the birth of their first daughter in 1842, and had a few children in Ireland before moving across to Monkwearmouth by Bridget’s birth in 1849. Bridget’s place and approximate year of birth remain consistent throughout her life, which is quite surprising, but I have not been able to find any GRO registration relating to her birth. There is a multitude of reasons that could lay behind this and are irrelevant to her life story, but I thought it was worth mentioning still.

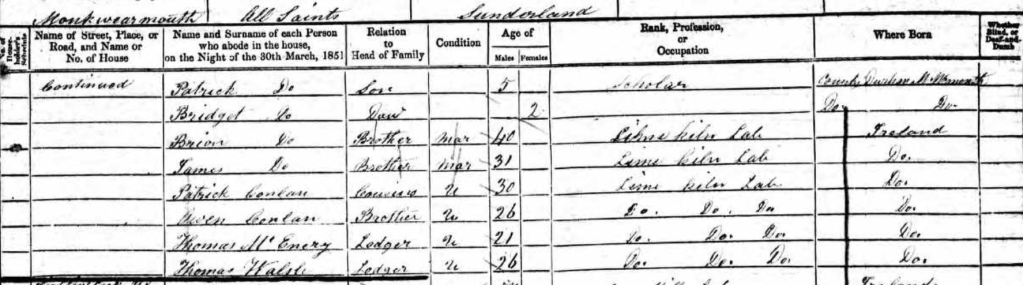

Growing up, Bridget had it tough, and nothing can illustrate this in a better way than the way her family was living in 1851, as there were eleven people residing in the Cook Household – including Bridget herself – on that year’s census. The family included Bridget’s parents and siblings, but she also lived with some lodgers – specifically George’s brother, some of her father’s cousins and two other unrelated men. Furthermore, there were another five people from another family residing in the same building, making 16 individuals.

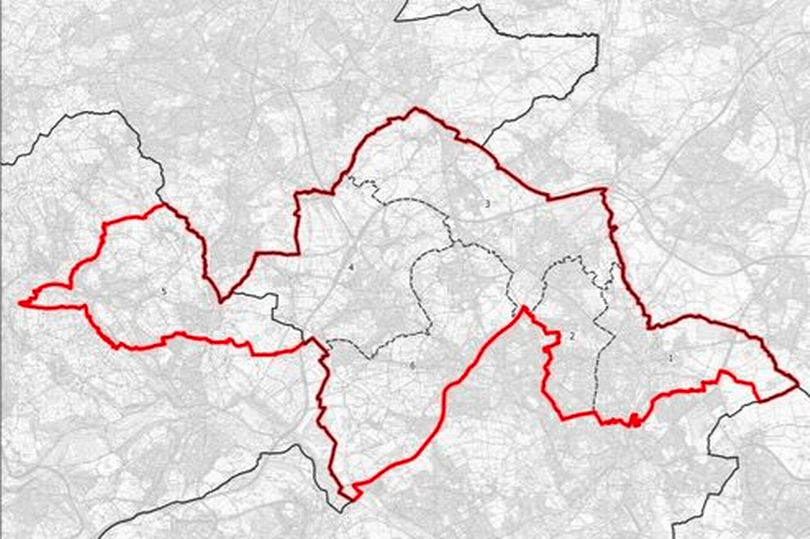

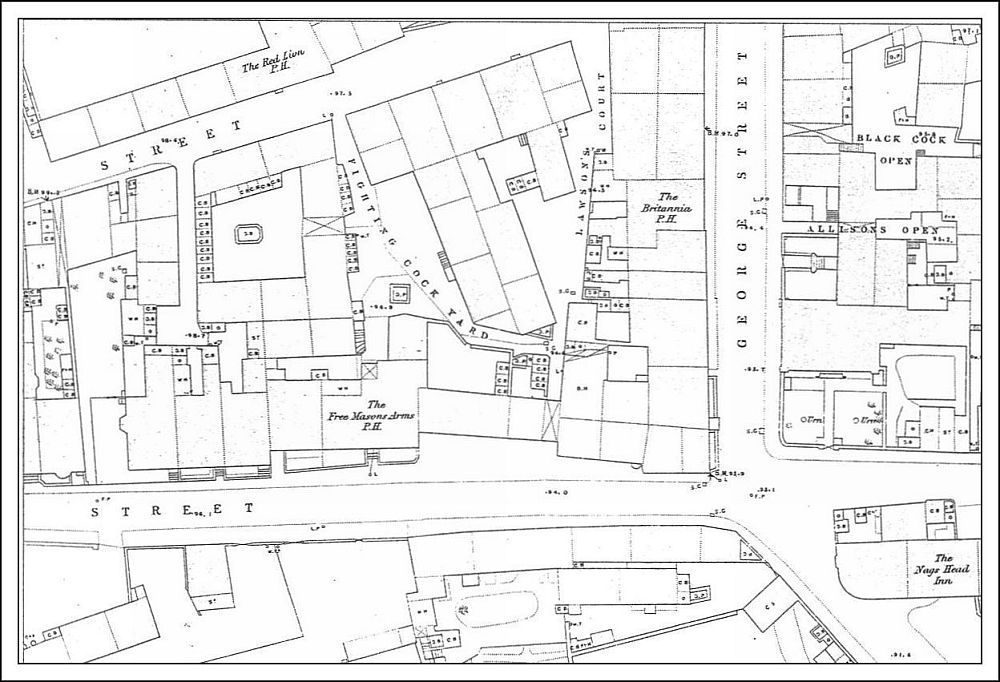

Another indication of just how tough Bridget’s childhood was where the family lived throughout the entirety of it – Fighting Cock Yard, near John Street. The same doesn’t sound inspiring, nor do the much later reports that crime was rife, including prostitution, clearly showing just how destitute and desperate its inhabitants were. Despite this, siblings followed – Mary Jane in 1856, George in 1858 and Julia in 1863. Julia was lucky to survive past her infancy, but sadly, both George and Mary Jane were not, dying when they were just over a year or a few months old.

By 1861, George’s earlier mentioned brother had finally moved out and got married. He lived with his children, mother, and wife on that year’s census but also an eighteen-year-old lodger, Charles McIlroy. He is key to Bridget’s story as they both got married in less than a decade. Specifically at St. Benet’s Roman Catholic Church in the second quarter of 1869. Her marriage to McIlroy ostensibly started reasonably well – she gave birth to a boy named Charles (perhaps after his father) exactly a year later. However, this was not to last.

Charles McIlroy was dead by the time of the 1871 Census, and I am clueless as to exactly when or how he died. Was it tragically before the birth of his son, leading to him becoming his son’s namesake, or did he get to see his little boy be born? I am unsure, as I said before, but I will always pray to myself that he did get to see him. Another significant loss struck in this period as Bridget’s mother, Judith, passed away in late Jan or early Feb 1870, aged only about 50, and was buried at the local Mere Knolls Cemetery on 3 February 1870. Aged only 21 or so, Bridget had seen the loss of two siblings, her mother and also her husband – this would rightly break so many people but not Bridget.

I think that Bridget was a woman of incredible courage and determination and was certainly not stupid, and her actions after the death of her husband and mother display this. She took on a leadership role, being recorded as the Head of the Household of 13 Fighting Cock Yard on the 1871 Census – residing with her son, some siblings, father and new stepmother. She was willing to work both domestically but also to make a living, gladly recording the fact she was working as a labourer in pottery. She didn’t let the many losses she was facing destroy her, she had every right to, but she and her family would also end up dead with her late husband and mother. Society and life were cruel, and if Bridget didn’t work, she would fall into the hardest of times, and she clearly wasn’t willing to accept that.

Her courage and ability to take charge of her own destiny at the pivotal moment allowed her to remarry and eventually pick herself up from her losses. She did this in late 1872 to a man named James Conley, who lived nearby on John Street. From this marriage, my Great Great Grandmother, Catherine Conley, was born in 1873, followed by George in 1875. There was an interruption to Catherine’s period of relative peace as she lost a son, namely James, who died aged about 19 months in 1878. Things looked up again as she gave birth to a healthy boy, Peter, in 1879, and then a girl, Mary Ann, in 1882.

By 1881, Bridget had finally left Fighting Cock Yard, residing at 38 Brook Street, with some other families alongside her husband, sister Julia and children. Sadly, her father had died some years earlier, in 1877, and Bridget had lost another key figure in her life. It is perhaps less tragic in nature as George Cook was advanced in his age, dying aged 60 or so, but still, despite leaving Fighting Cock Yard, she couldn’t avoid another bout of deaths.

Before she encountered another loss, she had two more children – John in 1885 and Julia in 1887. This subsequent loss was in spite of all her labouring and bravery, her eldest son Charles McIlroy, who had effectively been adopted into the Conley family, passed away on 26 April 1890 at the Conley family home of 18 Stobart Street due to complications from tuberculosis. Poignantly, James Conley registers his stepson’s death, showing that he was still willing to claim him even in death.

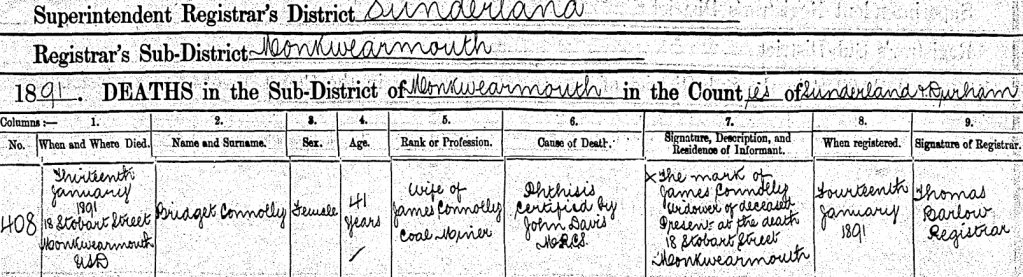

It all ended suddenly for Bridget, not so long after the birth of another daughter, Martha, in early January 1891. Years of toil, bravery and a burning desire to survive for the sake of her family all faded away due to the cruelty of tuberculosis. Like her son a year earlier, the disease killed Bridget on 13 January 1891 at home at 18 Stobart Street. Luckily, her husband, James, was present at her death.

Due to the fact her grandson, my Great Grandfather, was orphaned and difficulties surrounding finding her maiden name, Bridget’s story was at least temporarily lost to time. It was only recently uncovered in its true form, one of immense determination and bravery. This was in the face of a brutal society, appalling living and working conditions and countless unimaginable losses – Bridget Cook defied all odds and managed to keep her family and children alive for generations to come. Her story is genuinely inspiring to me, and I look to employ her spirit and memory as I progress through life.

For, if she had given up without much of a fight, would I be sat down writing her story 131 years after she passed away?