Back about seven years ago, in 2014, Britain marked Remembrance Day alongside the centenary of the outbreak of the First World War. I was only nine years old, so I naturally don’t remember a great deal from this time period; however, I do have some strangely distinct memories. We had an assembly on Remembrance Day, and towards the end, a video was played. I can’t remember at all what this video said or was about apart from it being related to Rememberance, of course. Towards the end, many photos of fallen soldiers were shown, which profoundly affected nine-year-old me. I suppose this was down to the fact that I was presented with the fact that the millions who died years ago were all human with aims, dreams, fears and hopes. As a kid, I was a sensitive soul, and I have no shame in saying that I had teary eyes walking back to class.

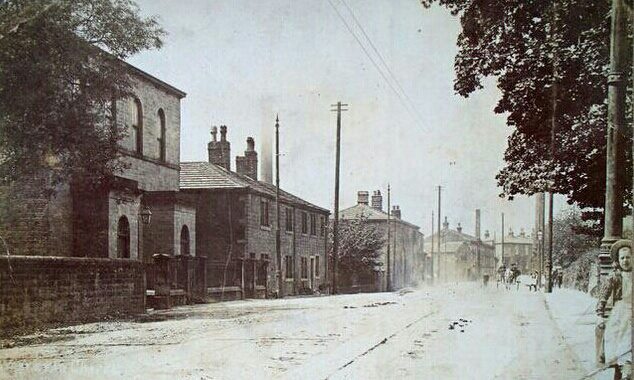

I always took Remembrance Day seriously subsequently, but it was a while before anything of significance happened. I joined the Air Cadets in 2017 and, because of this, partook in Poppy Selling and also marched at the Cleckheaton Remembrance Day parade.

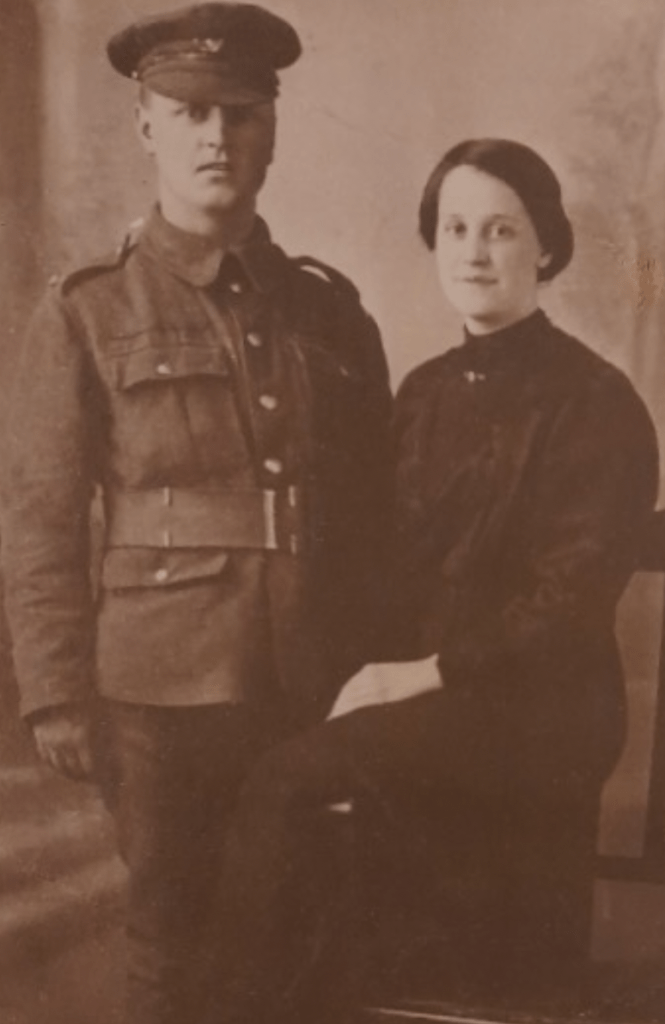

My genealogical research began in March 2020, just before the lockdown was announced, and I came across the story of my Great Great Great Uncle George Alfred Dale. I have told his story on a Hidden Branch blog post which can be found here, but I became deeply connected to George. I couldn’t for the life of me tell you why but I bought/searched anything to find out more about him. I was lucky enough to have a picture of him already uploaded onto Ancestry and, in the early months of 2021, found a second picture of him online. I suppose what attracted me to him was simply that he was the first soldier I had come across and the fact he made the ultimate sacrifice. Another reason is that I am, in a way, named after him as my Great Grandfather George Ronald Dale, who I am named after, was named after him.

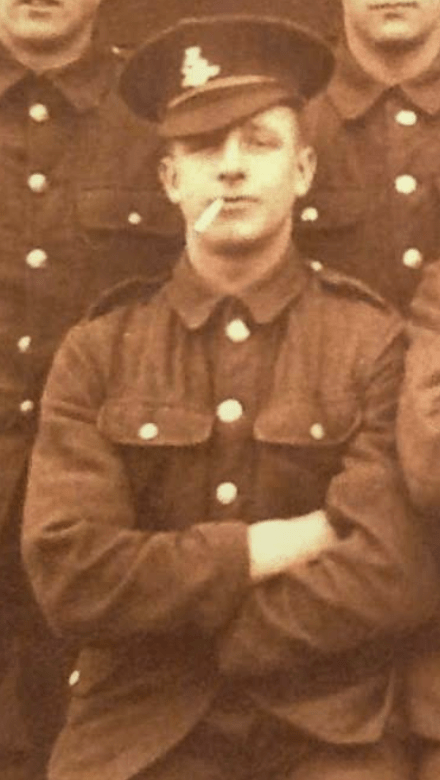

The next major story I uncovered was the service of my Great Great Grandfather Ernest James Hall. He was born in 1885 in Batley and had a rough childhood with a notorious alcoholic father. He married Emily Butcher in 1908, and the couple had seven children over their marriage. Ernest joined the 8th Battalion of the King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry at some point after the birth of his daughter Phyllis in 1915. He would have served across France but also Italy towards the end of the war. Quite a few of the Halls served in the First World War, including his nephew Walter and his brother Lewis with whom he appeared to enjoy a close relationship. Ernest was injured at some point in 1917 and suffered injuries to his sight, and was awarded a pension that lasted for about a year. He received the British War Medal, and Victory Medal, one of his medals was inherited by his son and my Great Grandfather Percy Hall. It remained displayed with pride by my Great Grandma even after my Great Grandfather’s death and is still in the family to this day. Ernest also sadly had PTSD, or as it was more commonly known at the time “shell shock” and kept himself to himself and rarely saw his grandchildren towards the end of his life.

Fred Hopkinson, another Great Great Grandfather, was born in 1896 in Birstall also served during the First World War. He joined the King’s Own Scottish Borders and served in a variety of different battalions and was sent to France in October 1915. In the summertime of 1916, he was injured, although the nature of the injury is unknown. He was awarded the British War Medal, Victory Medal and the 1914–15 Star. His experiences of the war were rarely mentioned, although my Great Grandmother Shirley, Fred’s only daughter, recounted that when he was in trenches, he was knee-deep in mud and water.

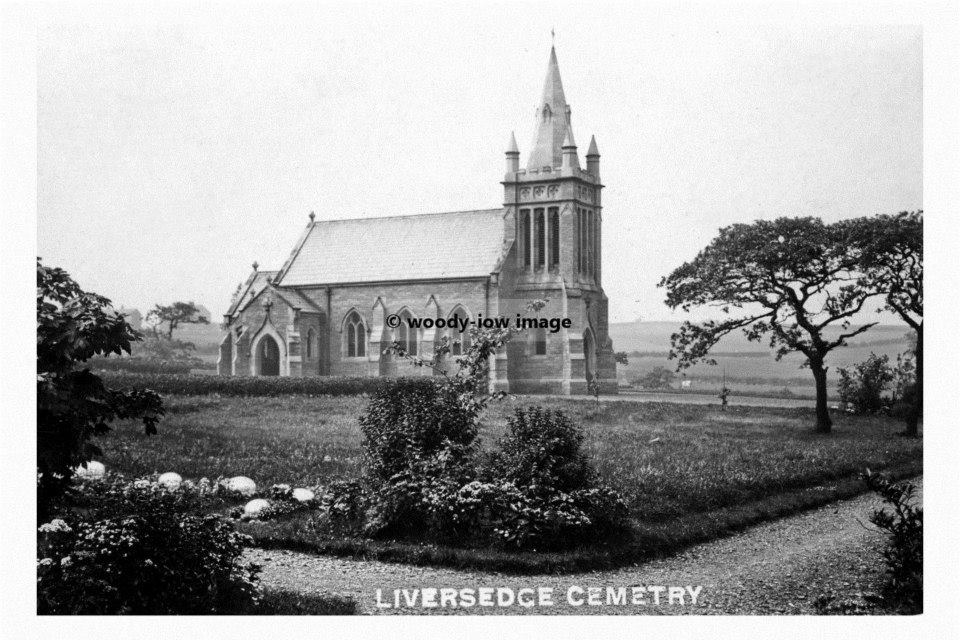

My final connection is a larger project I have undertaken, researching and writing up the stories of all 36 known soldiers buried/commemorated at Liversedge Cemetery. The book will be published relatively soon (all will be announced on my website and social media), but it has been an experience writing it. The sacrifices, bravery and selflessness of the wartime generation bled through the individual acts of bravery and sacrifices to provide a model that everyone should strive to follow in the modern-day.

Remembrance Day means a lot more to me than it did before, and I hope that this can prove to you that there are many different ways to engage with remembrance. I haven’t even mentioned any of my Great Grandfathers that served during the Second World War or that of their siblings, both male and female, who contributed and made sacrifices to the war effort in their different ways. It is essential that we remember our fallen troops just as much as the ones who lived with the consequences of their service up until their passing. We must also ensure that in 100 years, Rememberance remains as significant as today and 100 years ago as if we forget, we are doomed to repeat.