Now, to understand the proper context behind this incident, I’d ensure you have read about the 1905 incident.

To start, we have to discuss an ending, more specifically the death of Mr. Joseph Brook. Prior to his passing, he resided at 38 Pyrah Street off Carlton Road in Dewsbury and was employed for many years at the woollen manufacturers Messrs. Mark Oldroyd and Sons Ltd. He married Emma Ellis in 1872, and they went to have five children that survived infancy, with at least three passing away in their childhoods. Out of the five surviving children, there were four girls and one boy.

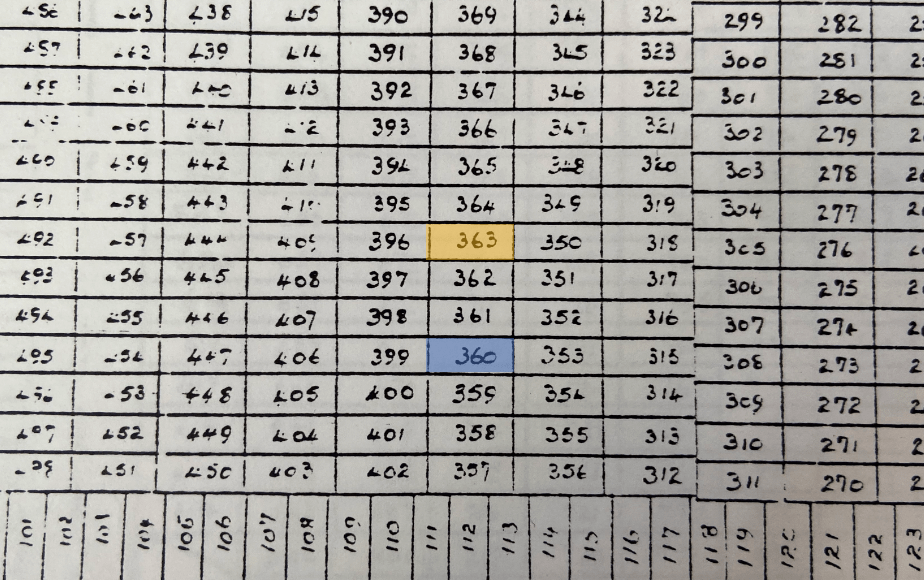

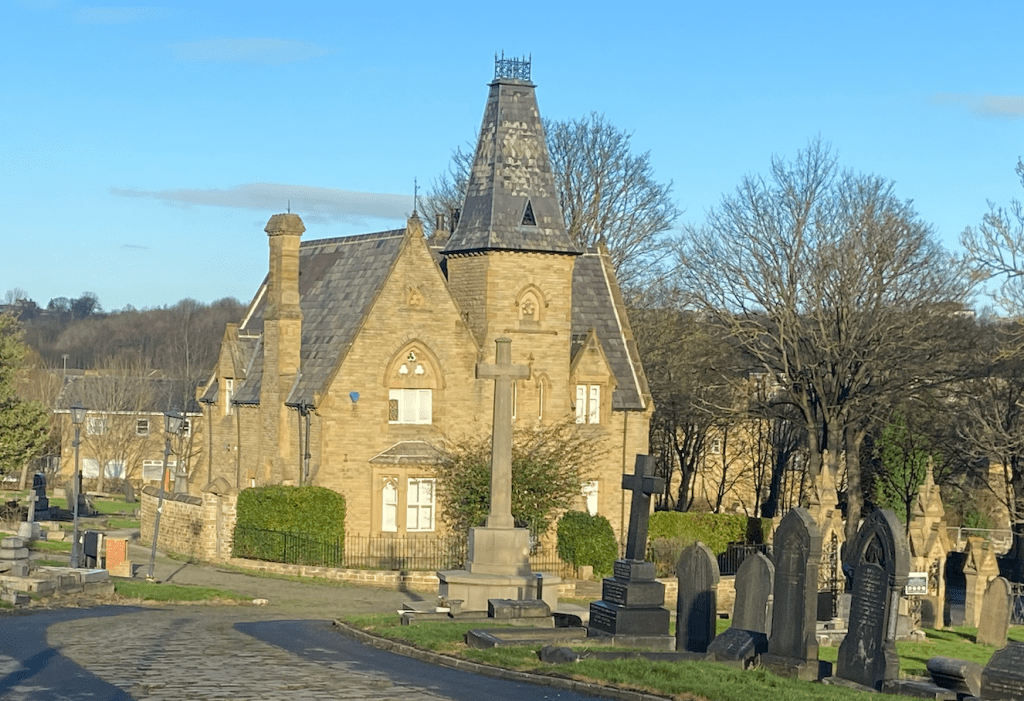

However, his health began to decline in 1907, and he was unable to work regularly and passed away on 7 August 1907, aged 56 years. He was interred in a plot at Batley Cemetery with three of his deceased children three days later. The funeral was a large one, attended by more people than the Chapel could accommodate, and everything passed satisfactorily.

The day after Joseph’s funeral, alongside one of her daughters, Mrs. Brooke visited the cemetery. She wanted to ensure that the grave had been filled in and to have a look around and perhaps visit her husband.

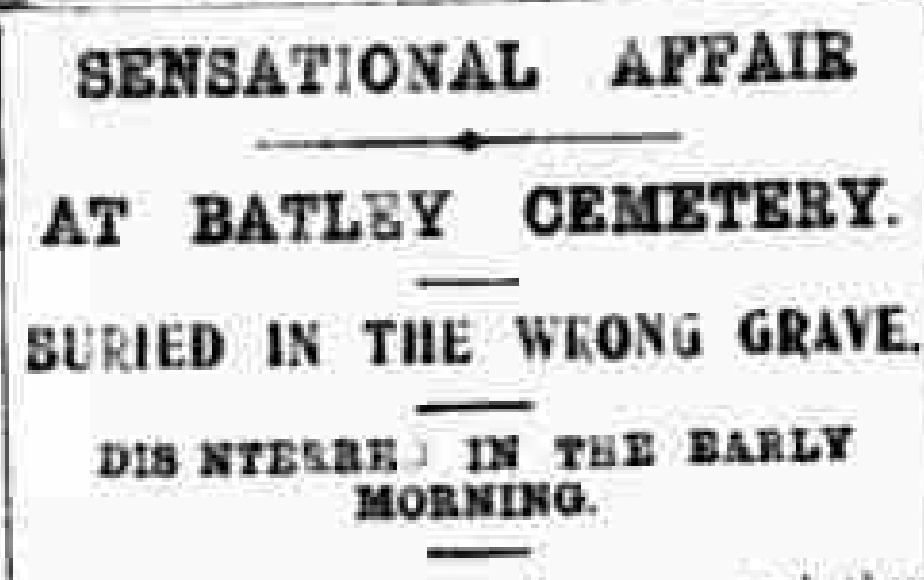

In an almost familiar scene to that of Mr. Marsden’s visit in 1905, Mrs. Brooke instantly sensed something was wrong, remarking to her daughter that she was certain that her father was buried in the wrong grave. Again, a certain type of tile surrounded the grave, and Mrs. Brooke noted it was not disturbed.

Now convinced the error had been made, Mrs. Brooke was unsure what to do. Naturally, this deeply disturbed her, and she was unable to sleep at night. Not only had she lost her husband, the breadwinner, and had four children to look after, but she now had to sort out this error. Finally, about five or six days after the burial, after taking some advice, she decided that the best course of action would be to head to the cemetery lodge and talk to the Registrar, Mr. William Henry Atkinson.

Atkinson didn’t believe her at first but was willing to check to ensure a mistake hadn’t been made. It quickly became apparent that Mrs. Brooke was correct in her assessment, and Mr. Brooke’s almost perfect funeral had one fatal flaw. He was buried in the wrong grave.

The Cemetery Registrar immediately expressed his deep regret to Mrs. Brooke and promised her the incident would be sorted. Afterwards, Mrs. Brooke communicated with a Town Council member and the Deputy Clerk of the Council, with the latter being contacted as the Town Clerk himself was away. She was even advised to contact the Mayor (Cllr. W. J. Ineson), who assured her that everything would be sorted in a satisfactory manner without a doubt.

This greatly comforted Mrs. Brooke but being a woman of incredible grit and steel, she refused to rest until her objective was met, continuing to contact the relevant bodies for the next week.

A short while passed, and it was reported that the Home Office had been contacted and that the official form required for the reinterment had been received. However, owing to the typical bureaucratic nature of government agencies, it took a while to arrive. Furthermore, it was reported that Mrs. Brooke and her family were satisfied that everything was being done to rectify the mistake.

Eventually, on 29 August 1907, the permit for the reinterment of Mr. Brooke was received in Batley. The following day at 6 am, Mr. Brooke was interred into the correct grave, finally resting with his three deceased children. Mrs Brooke, the driving force in ensuring the mistake was rectified, alongside three other family members and various representatives of the council and Atkinson, the Cemetery Registrar.

The incident is a testament to the courage, determination and perseverance of Mrs. Brooke. After all that she had been through, she had managed to get it sorted. However, the incident also shows the impact of the 1905 incident as everything is done “above board” with no chance of any legal comeback.

With that comes the end of my interest in these two very unnecessary and unfortunate incidents in 1905 and 1907. Unfortunately, I know for a fact that incidents like this would continue up until at least the 1990s, if not the present day. I suppose this is a sad reality that we must face, but it seems so cruel that families have to face these incidents in times of grief.