Sometimes, when I walk the dog or cut the pizzas at work, I will come up with ideas for the blog. It was around last Monday as I write this when I considered looking at the long line of Georges, basically looking at how the name was probably passed down the family for at least nearly three hundred years. From Newcastle to York to Batley and then finally Liversedge. I wanted to dive into how the name stood up in times of conflict and suffered through generations of strife and loss.

Jumping forwards to Thursday now, I got up early (well, early for the school holidays) at around nine and took the dog out for a walk. It was strange weather that day, ranging from snow to sun to hail. It had just started the snowing part when I checked BBC news and realised that Putin had done the unthinkable and plunged Europe back into war. I have no shame in saying I felt physically sick.

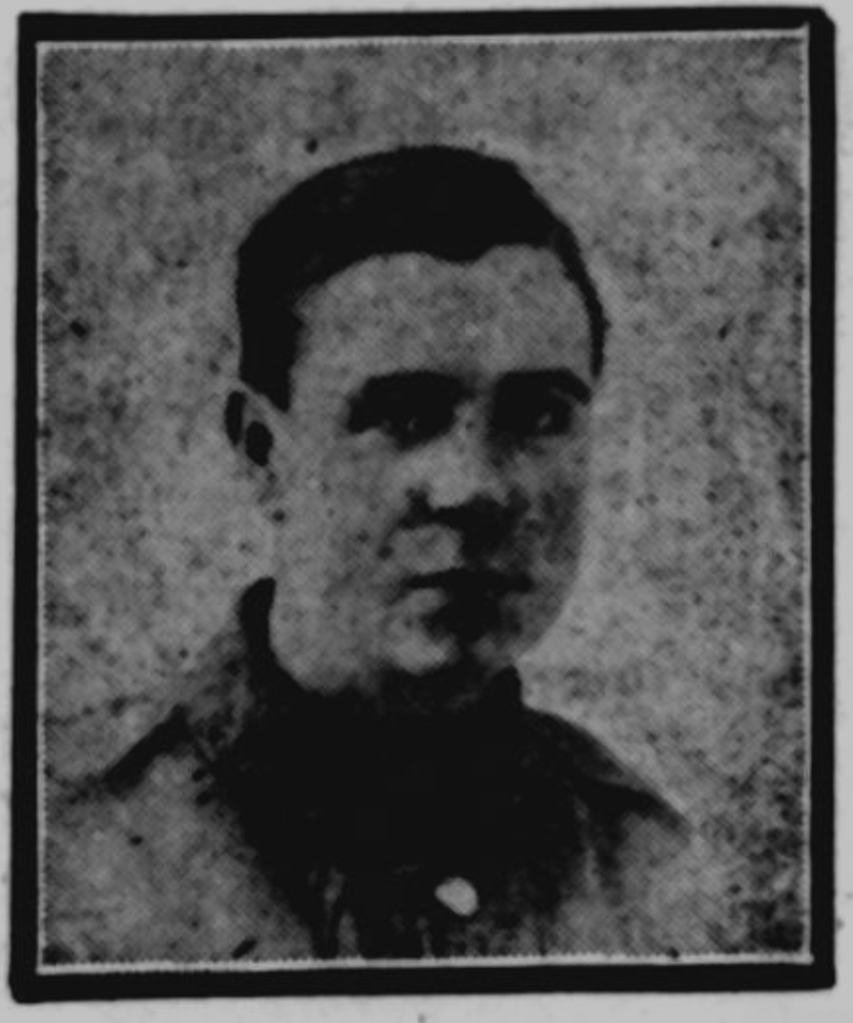

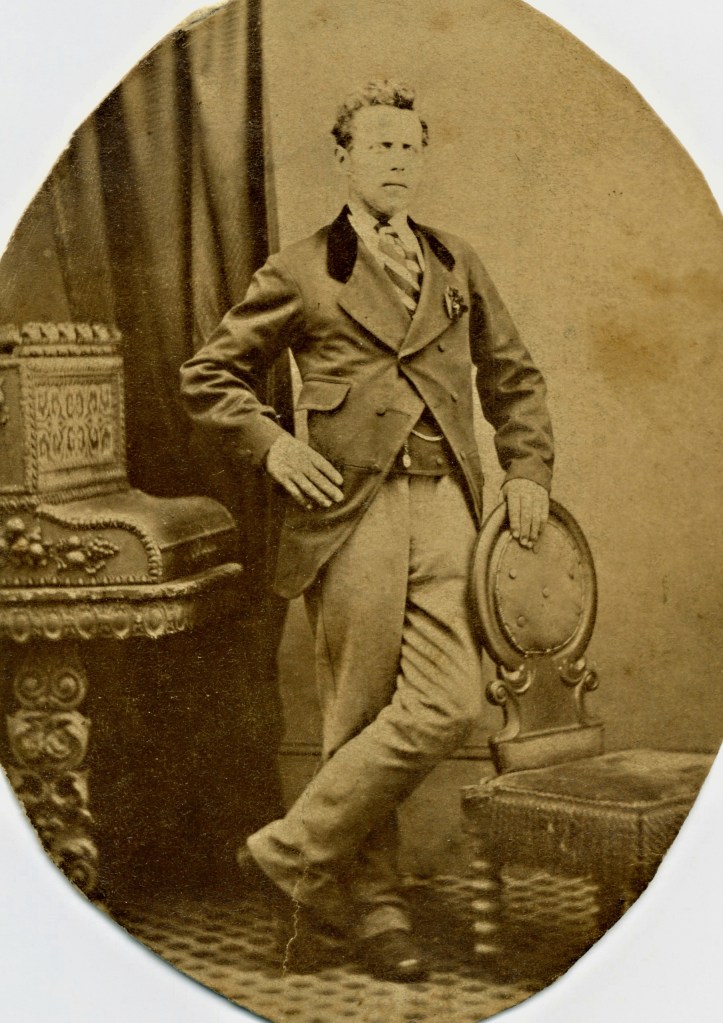

George Alfred Dale, my Great Grandad’s uncle, is someone who I deeply look up to and, in the strangest of ways, love. He was the first lad that I came across in my family tree that made the ultimate sacrifice in the First World War. There was a fair bit of information on him, and also, luckily, there was an ace photo of him uploaded onto Ancestry. I wrote my second Hidden Branch Blog post on his life, and he is also mentioned in my Remembrance Day post. Furthermore, I recently wrote a second biography of him, really weaving in some more personal thoughts and feelings and submitted it to my School’s creative writing competition.

G. A. Dale enlisted underaged, and the horrors he must have seen are unthinkable. Villages, towns, homes destroyed, men mutilated or killed on a daily. As a lad of my age, he saw the worst of humanity – death, destruction, and cruelty in its most naked form. We will never his exact own thoughts and experiences, but it is genuinely unthinkable what his generation experienced, only to be repeated by the next one.

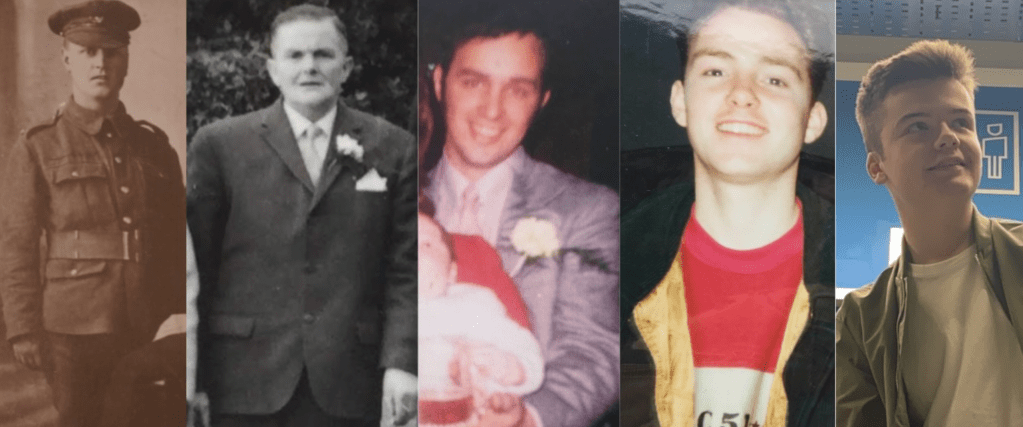

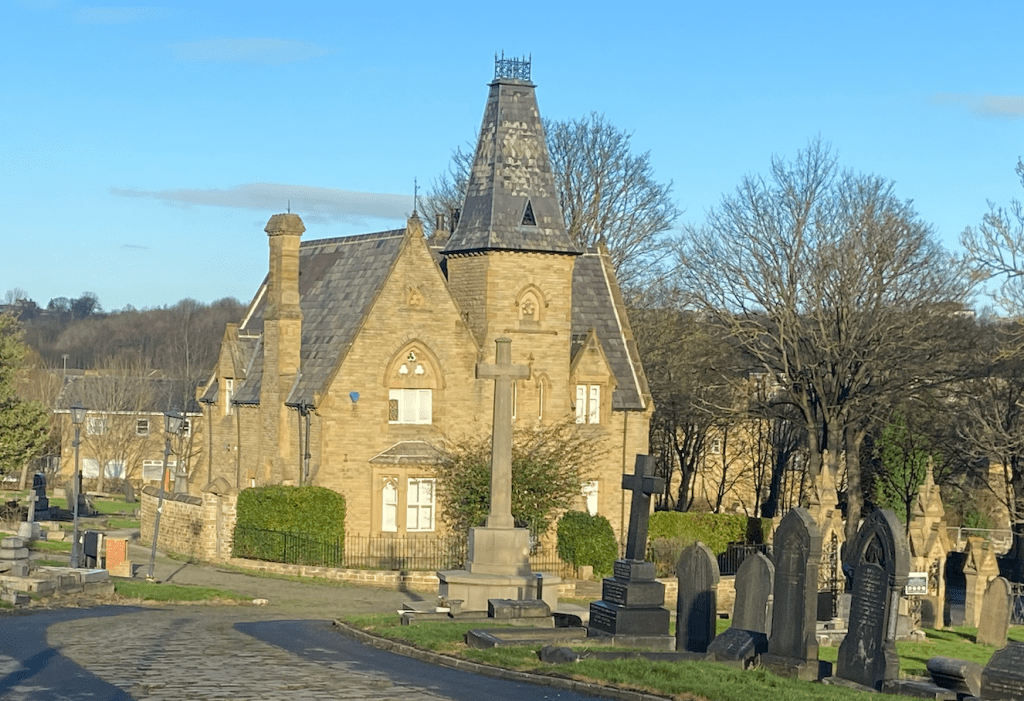

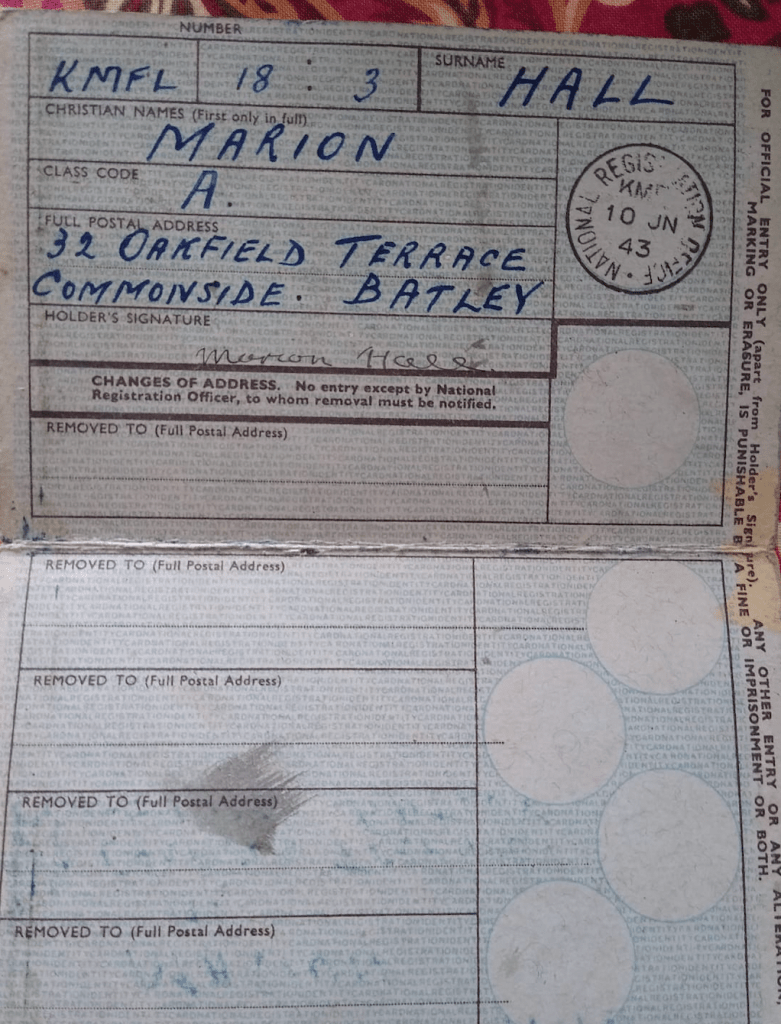

My Great Grandfather, George Ronald Dale, was a kind man that I unfortunately never got to meet. I have quite literally never heard a bad word said about him. He worked most of his years at Batley Park, but due to the fascist terror spreading across Europe and during the late 30s and early 40s, he ended up serving just like his uncle George.

He joined up in March 1941, just after turning twenty, and served with the Royal Signals, eventually serving across France and the Netherlands. He worked his way up to the rank of Corporal and was also very physically fit, helping run a fitness camp in Ossett at some point during his service. He was a little older than his uncle but again likely saw the worst of humanity as he helped liberate Europe from its Nazi tranny.

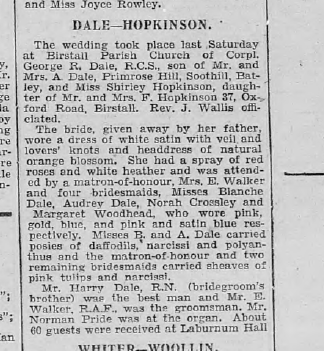

Whether they were a woman, man or child, everyone made sacrifices and took part in the war effort, and this was clear as crustal when it came to my Great Grandad George’s marriage. He married Shirley Hopkinson, another kind and loving soul, at Birstall Parish Church in 1944. George’s brother Harry was his best man and also served in the Royal Navy. I guess the war shadowed even the supposed happiest day of his life to an extent. I can only think of the dread that those left at home must have felt every morning waiting to hear in case the worst had happened. Imagine also looking forward to your wedding and your future with your sweetheart while fighting a war.

It is almost unthinkable.

But there I was, almost glued to Twitter, the BBC News website or Facebook, watching the human tragedy unfold. I do not wish to be political, but it is as clear as day that the war which is unfolding is all things said above; cruel, unnecessary and the worst of humankind. Whether they be a soldier or civilian, each fallen person is another soul lost to war.

It seems ironic and poignant that I wanted to discuss this. Still, regardless of what happens across the world, this legacy of loss associated with the name George in my family has hopefully faded away. The wars experienced by my great grandfather and his uncle made strong, courageous men willing to give everything for those they loved in the face of the worst. It is truly inspiring to me to be related and directly connect to those two men.

I will leave you with a simple statement from the memorial book at Dewsbury crematorium after my Great Grandfather’s death in 1987. Although written for my great grandfather, words that very much apply to his uncle George.

“Courageous in Life and Death. Gentle, Kind, and much loved”.