Liquid sewage once ran down the surface of Heckmondwike’s footpaths. Dead pigs lay rotting a mere six feet from people’s front doors. These front doors opened to small and ill-ventilated rooms. Public health was in dire straits. By the 1840s, things became even more dire as the wells that provided the town’s water supply started to dry up and become contaminated. There was a desperate need for action. A desperate need for change.

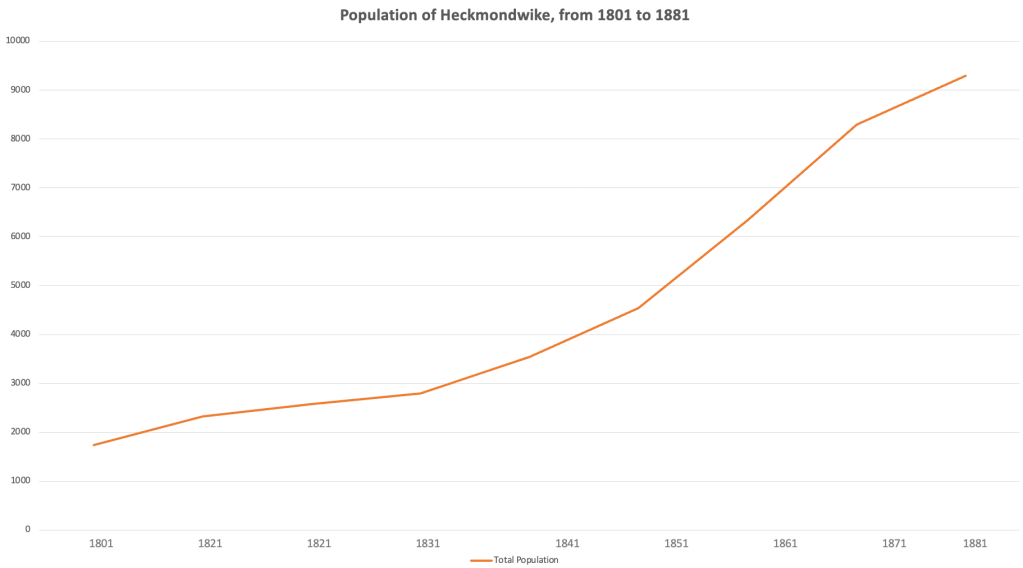

Heckmondwike’s population rose dramatically throughout the Georgian and early Victorian period, doubling from 1,741 in 1801 to 3,537 in 1841. This coincided with the Industrial Revolution and its significant social and economic changes. In specific regard to the water supply, not only was there an increased demand from the population but there was also a need to supply both the new mills in some form. Moreover, wells used by the general population began to dry up due to the sinking of deep coal pits, which led to increased demand and decreased supply.

We can look at later testimony to bring home how bad things became.

In the 1852 inquiry, Mr. Crabtree describes how, during an extended drought in the spring of 1852, people had been obliged to get water from a colliery, and the owner made them pay for the privilege. He had even known when his house had been without a drop of water. Another gentleman had spent 6 pence a week for his water for over two years, and he had to wake up at 6 am to carry the water for a quarter of a mile home. Quality became irrelevant, and some people, such as Mr. J. Wood, fetched his water supply from a pond where cattle drank. The richer you got, the higher the chance you had a private well or pump that supplied some water, but even these began to dry up.

A solution was not straightforward, though.

At the same time, a larger societal debate surrounding public health occurred across the country as groups began to argue for greater spending towards and institutional regulation of public health. It was, for many, less of a moral crusade but one focused through a lens of spending efficiently. The logic was that many people reliant upon poor relief only became so due to the dire state of public health. This, alongside fierce campaigning and another cholera outbreak in 1848, led to the Public Health Act.

The Act allowed the creation of local-based authorities that could fund the development of new local infrastructure and enforce public health standards. This Act did not compel its adoption, and in many places, such as Heckmondwike, where local government structures were to some degree outdated or lacking, whole new structures would have to be created. This was not necessarily popular, and Heckmondwike seemed sceptical about adopting the Act.

However, irrespective of the town’s political desires, the crisis continued to cause misery, and as water quality dropped, mortality rates increased. By 1849, local leaders were spurred into action by a nasty outbreak of cholera. They gathered and decided to try to raise £2000 to create a public company to supply water for the residents of Heckmondwike. The scheme was met with apathy or opposition, with just £700 raised despite an extensive public campaign. It may be speculative to point out, but it is interesting to note that those wealthier residents who would have been needed to contribute to the scheme likely already made a profit from the population relying upon them for water supply.

After the initial attempt at creating a public company failed, a petition was sent to the Board of Health to adopt parts of the 1848 Act surrounding water supply. There was still some hesitation in the need for this new public institution. The government replied that the Act had to be adopted fully, and the petition was rejected.

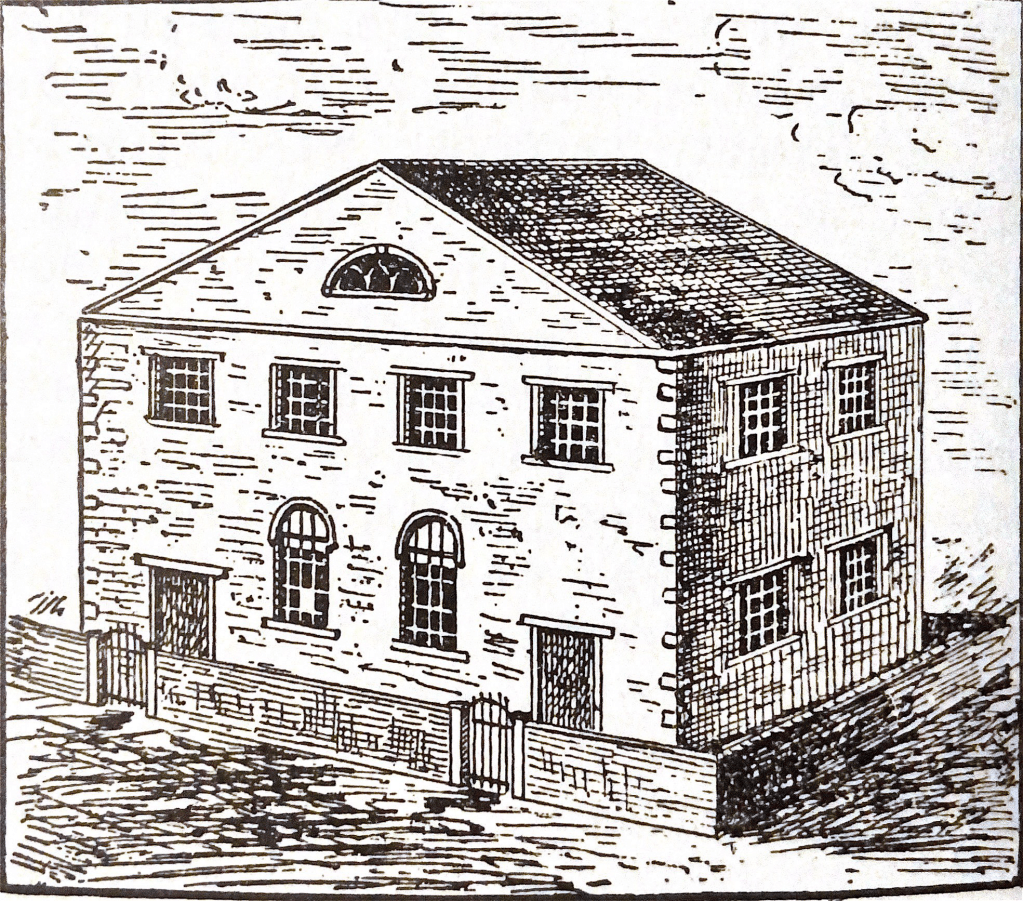

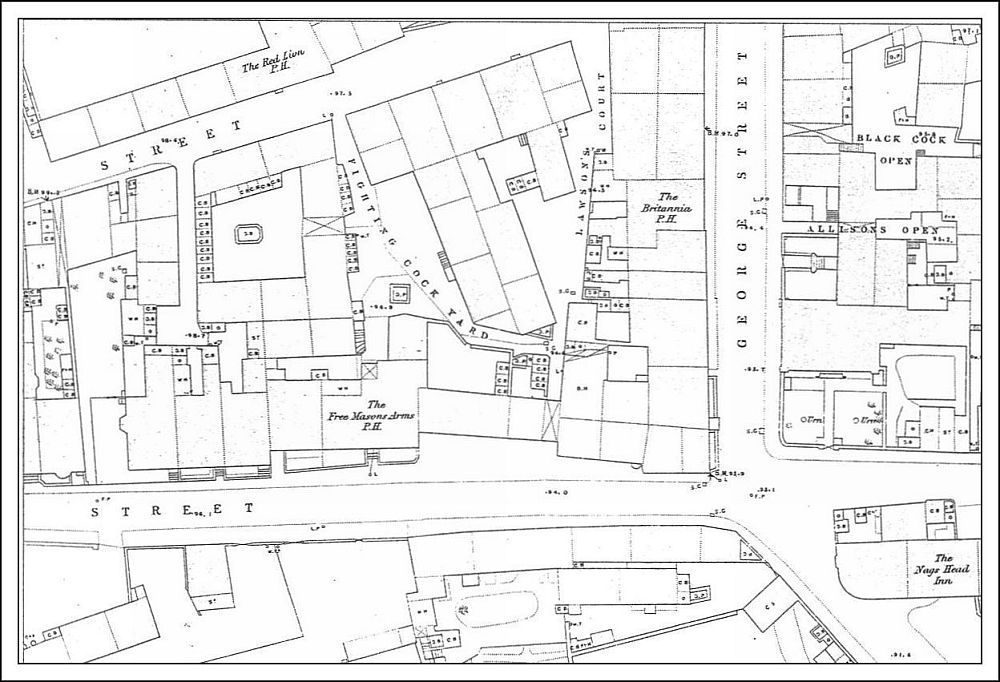

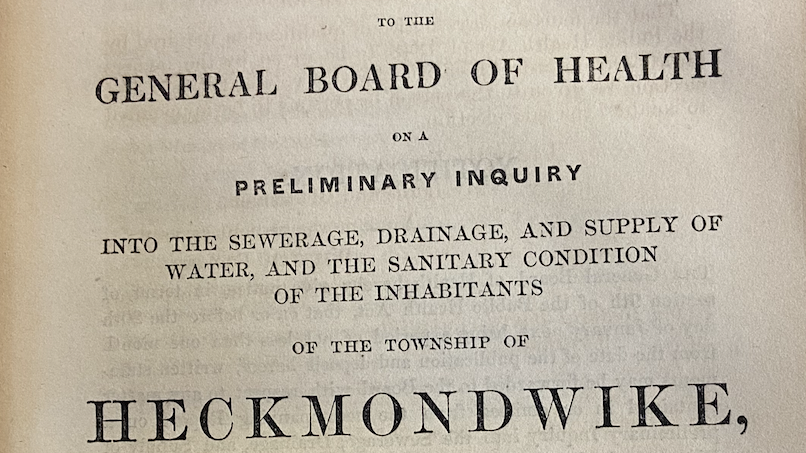

Action was taken again in January 1852, when just over a hundred Heckmondwike ratepayers sent a new petition to London to hold an inquiry to adopt the Act and form a Local Board of Health. A public inquiry was held over two days starting on Wednesday, 30th June. William Ranger was sent to lead an inquiry based in the Freemason’s Hall. Sessions took place during the day and also during the evening to allow working people to attend and give their evidence. Ranger notes that attendance was quite high, especially in the evening.

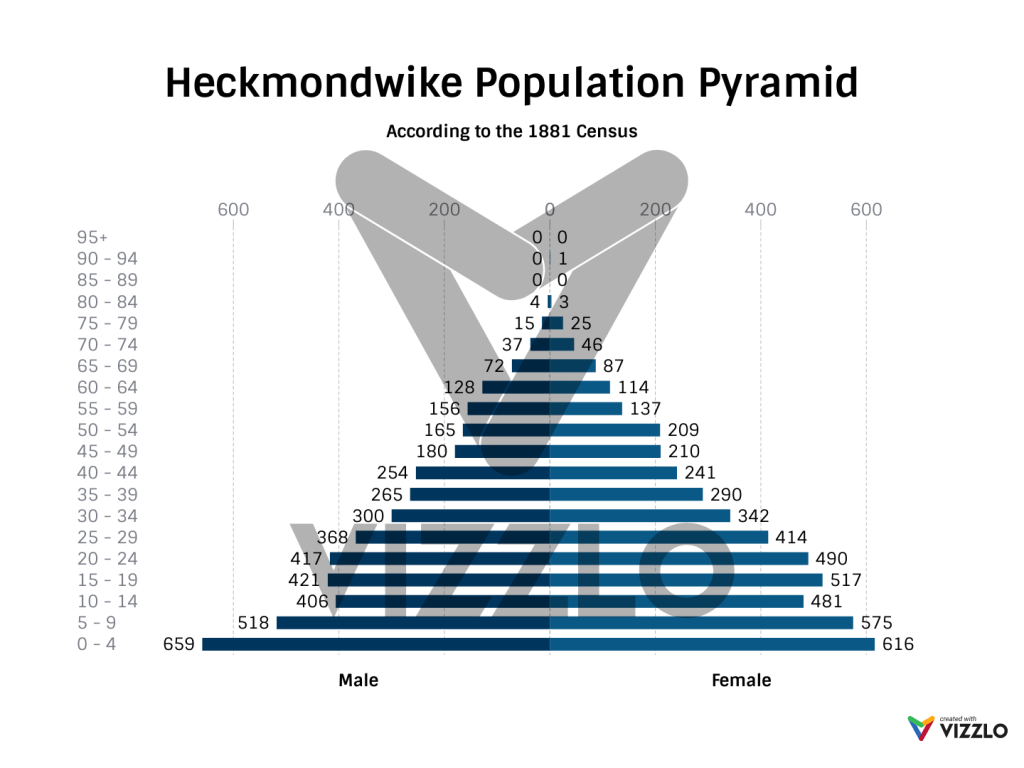

According to the injury’s report, in 1851, Heckmondwike had a population of 4,540, an increase of just over a thousand in ten years. The gender divide wasn’t significant, with just 70 more men than women. The town had 939 houses, which led to an average of 4.8 people per house.

The town had the following:

- Seven woollen mills

- One corn mill

- Two carpet and coverlet mills

- One dye work

- One foundry

- One railway

- Five coal mines

Local government was not formalised in a way we would recognise it. A mix of antiquated roles and more modern roles administered the town. There was a general feeling from many that those in positions of power could not enact any meaningful changes to help the sanitary condition of the town. They lacked the power of enforcement through legal means. In many ways, it was solely down to those who built and owned land, buildings, and other infrastructure to maintain them to high standards.

“The respiration of pure air is essential to health, but the occupants of these places do not know what such a thing is.”

Housing conditions were dire. There is no other way to describe what people lived in. “Not fit for human habitation” was a quote regularly said by people of all classes and perspectives throughout the inquiry.

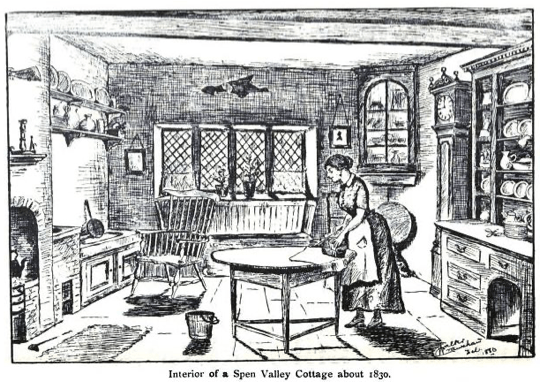

Frank Peel’s drawing of a typical 1830s Spen Valley cottage seems somewhat homely and inviting at first glance, but this was very far from the truth. An average cottage had little more than two rooms – a living space and a bedroom. Windows of the cottages were generally too small, and many of the bedrooms lacked fireplaces. Ventilation was, therefore, relatively poor. Cottages are described by one local man as “small, close, confined, ill-ventilated”, with a significant emphasis placed on the “accumulations of decomposing refuse” filling the rooms. A constant, aching reminder of the squalor people lived beside.

People did not have easy access to privy (or toilet) accommodation. This was especially the case in the older parts of the town, where if any accommodation was provided, it was in a deficient state. The Reverend E. N. Carter stated that in the neighbourhood of his parsonage in Heckmondwike, there were 23 houses, each occupied by a separate family, and only two privies for shared use, which were also described as “very dirty”. If we apply the earlier stated average of 4.8 people per house, this equals 55 people per toilet. Furthermore, Valentine Newsome, who lived in Chapel Lane, describes his area as having a “great want of privy accommodation”, including in his own property. However, his landlord refused to let any be built, no matter who funded it. Landlords and property owners could seemingly get away with whatever they wanted to and face no repercussions.

“The least and defective sewage in the localities where it is most absolutely required”

Spen Beck received the majority of the town’s sewage, but there was no sewage system in place to get it there. Mr. A. Goodall stated that from where he lived, “the yard leading from Goose-hill to Hill-house,” the houses at the upper end were without any drainage. This led to liquid refuse running over the surface of the footpaths. Moreover, if there was no privy accommodation at all, such as in the twelve houses on Post Office Lane, waste had to be thrown out of windows onto the street.

In an unnamed part of the town, fourteen houses had one privy attached to them. This was within five yards of a public well, which ended up being regularly contaminated and nearly impossible to clean. This could lead to infectious diseases, at times, running rampant through more working-class areas of the town.

It was not just sewage though as there was no formal refuse collection nor any standards enforced. This lack of regulation led to situations such as Mr. J. Walshaw’s where, outside his door, he described accumulations of refuse matter of every description. Dead pigs and offal remained outside just 6 feet from his door. Butchers were perfectly fine killing animals in their own yards, and in some residential parts of the town, pigsties stood nearby raw sewage.

It is hard to imagine walking through Heckmondwike town centre now with liquid sewage running past you, rotting pigs in the corner of the road, and people being forced to throw excrement out of their windows, but nearly 175 years ago, this was the norm.

This did not mean that people were mucky either. Heckmondwike’s population was proud, and William Ranger makes special mention of how those from the poorest of backgrounds in the direst of living conditions committed their most strenuous efforts to maintain some level of cleanliness when possible. However, through a lack of regulation and any serious means of redress against private property owners, Heckmondwike was a wild west of muck and disease.

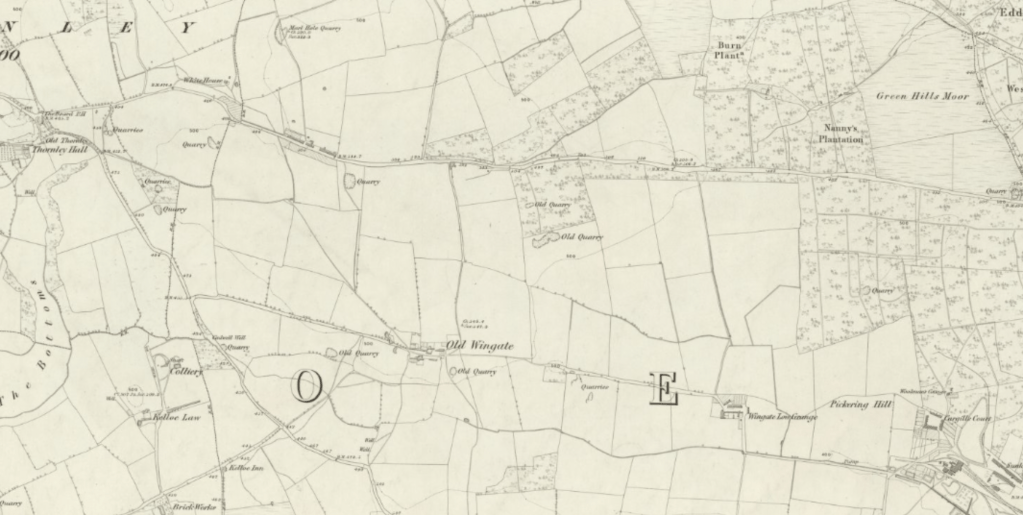

William Ranger recommended the establishment of a Local Board of Health, which was first elected in 1853. This body would reconstitute itself into the Heckmondwike Urban District Council in the 1890s before being absorbed by Kirklees in the 1970s. Heckmondwike was the first part of the Spen Valley to adopt the Act. Heckmondwike was recommended by Ranger to join the Batley and Dewsbury waterworks scheme. This had many ups and downs, but eventually, within a decade or so, water was finally provided to the town’s residents. The enforcement of public health standards began as regulations came into effect and practical actions such as building Heckmondwike Cemetery to ensure there was enough burial space were taken.

Heckmondwike would, in the following decades, become a pioneer of the new institutions, such as School Boards, which were established by Westminster Acts of Parliament. They would push them to their boundaries, and slowly but surely, the Local Board became an established and respected part of the town. Of course, to say one body of middle-class men truly changed the experiences of working people across the town is quite naive, but problems did begin to be resolved.

Bibliography

Peel, Frank. 1893. Spen Valley, Past and Present.

Ranger, William. 1852. Report to the General Board of Health on a Preliminary Inquiry into the Sewerage, Drainage, and Supply of Water, and the Sanitary Condition of the Inhabitants of the Township of Heckmondwike, in the West Riding of Yorkshire. London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office.

UK Parliament . 2024. “The 1848 Public Health Act.” UK Parliament. 2024. https://www.parliament.uk/about/living-heritage/transformingsociety/towncountry/towns/tyne-and-wear-case-study/about-the-group/public-administration/the-1848-public-health-act/.